Assembly Fellowship • May 2020 • DISINFORMATION

Filling the Data Void

By EC, Rafiq Copeland, Jenny Fan and Tanay Jaeel

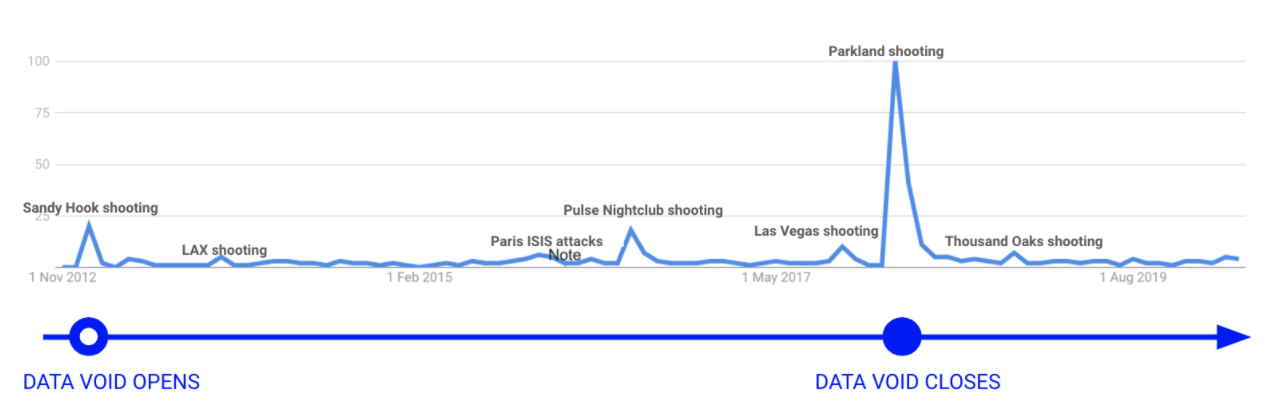

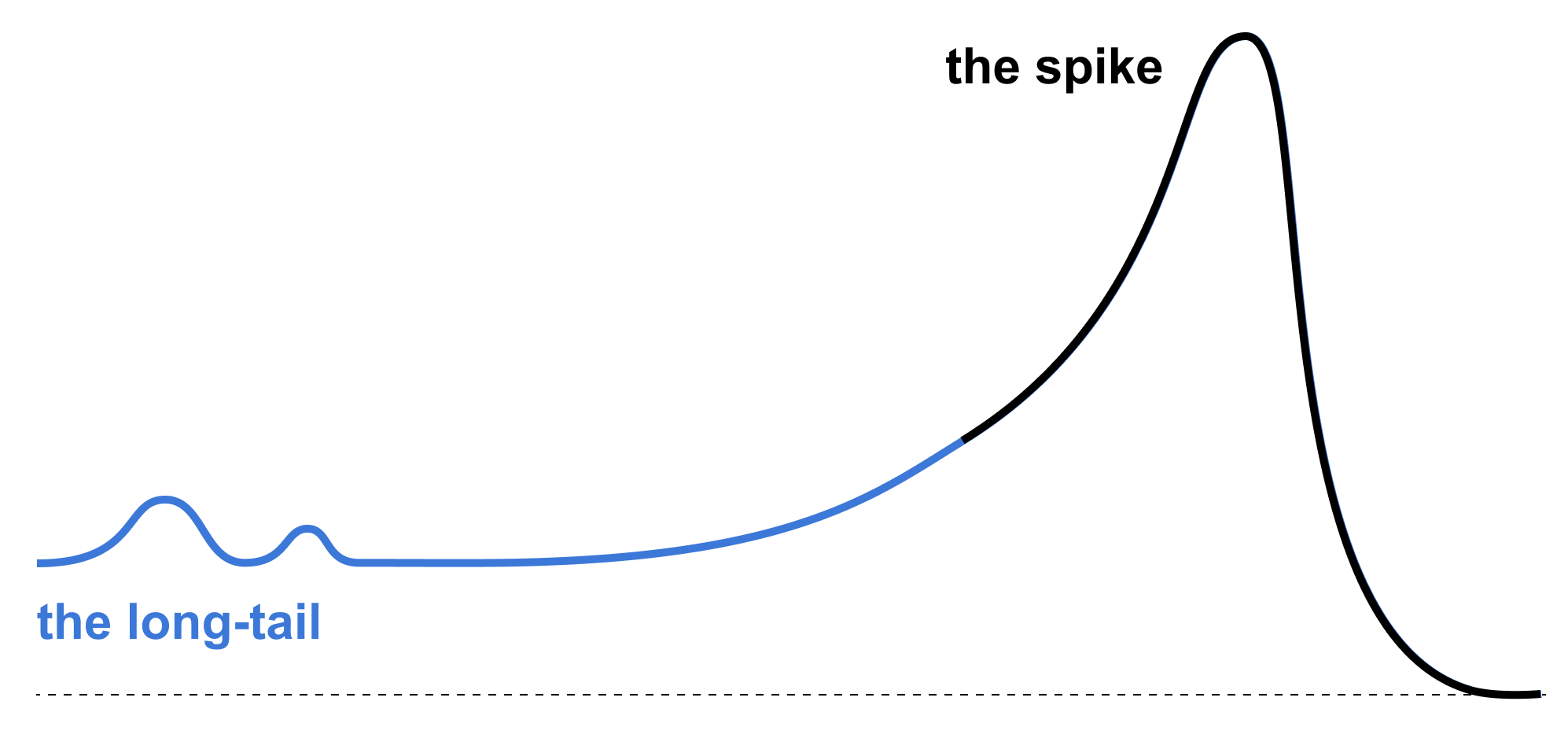

The risks posed by “data voids” – the absence of high-quality, authoritative sources in search results – have only recently been explored in the context of disinformation. As gatekeepers to the information ecosystem that are both collaboratively created from public contributions, Google and Wikipedia (which features prominently in search results) are vulnerable to media manipulators seeking to distort the narrative. This project aims to add more structure and empirical data to the understanding of this challenge with: 1) a Harms Framework to evaluate existing and emerging data voids, and 2) a data-driven method to map the life cycle of data voids across Google search trends, Mediacloud journalistic coverage, and Wikipedia page edits. The life cycle timelines point to a distinction between the "interest spikes" of breaking news data voids, which are quickly filled by mainstream news coverage, and more "long tail" data voids which persist over time and slowly accumulate problematic content. The timelines also highlight the interconnected relationship between mainstream media coverage and organic search in both covering and amplifying disinformation messages, and reinforce Wikipedia's role as a potential future battleground for disinformation campaigns. By providing a theoretical framework on how to assess emerging data voids and a programmatic script to analyze cross-platform media coverage, we are able to better understand the scope of the problem. However, this opens up a number of questions and areas for future research on how to appropriately develop policy responses to address emerging data voids.

Monday, February 3rd was a tough day for the Iowa Democratic Caucus. A glitch in a recently launched app to report results meant that voting outcomes were significantly delayed. While the US waited with baited breath, a narrative started to emerge that the faulty app was indicative of vote rigging. The conspiracy theory was encouraged by prominent political figures and news outlets which led people to search for information online about “Iowa Caucuses Rigged.” This in turn, led to claims that in the absence of credible, authoritative information that the Iowa Caucuses were not rigged, conspiracy theorists and propagandists successfully hijacked public discourse. Pushing a fringe narrative during such a crucial moment in the US’s political calendar would surely undermine the eventual election results and erode people’s trust in democratic processes.

This and other recent events have ignited questions in American society on how users search for and are influenced by information. From civic trust during the Iowa Caucus to public health and safety during COVID-19, concerns have been raised over the presence of misinformation within important social and political issues, and to what extent this misinformation hijacks the public narrative when credible information is not available to balance it out.

This phenomenon has a name within academic circles: a data void, or lack of readily available, credible, authoritative information relating to a specific topic (Gobeliewski & boyd 2019). In this paper, we set out to better understand the concept of data voids, specifically:

- What is the current framing around data voids?

- How should we think about the harms posed by data voids?

- What data exists to measure and further understand data voids?

Background: How information search works

Before we dive into these questions and into data voids, however, it's important to first step back and understand how users seek and receive information online.

Before search engines, information search online required much more user-directed methods that offered greater transparency and control at the cost of effort, such as looking up indices manually (Caroll 2014). The invention and popularization of search engines solidified its position as a ubiquitous and indispensable way to navigate the world wide web (Strategic Direction 2014). Google alone is responsible for 87% of all searches online (Caroll 2014), and this important role as both gatekeeper and intermediary has not gone unmissed (Clement 2020).

By design, search relies on a "vast ecosystem of networked information that is both created and ordered by a crowd of contributors", and search engines rely on proprietary algorithms to present the most relevant content (Graham 2013). This system is held together by high user trust: to cope with the sheer volume of information, most users process search results heuristically rather than systematically, assuming that highly ranked results are automatically more credible and authoritative (Werner 2007).

For the most part, the information ecosystem has indeed been optimized over time for credible, authoritative information. Google Search has made several changes over the last few years to optimize it’s ranking algorithms for relevance and quality. Webpages that potentially spread hate, cause harm, misinform, or deceive users are rated as not authoritative or trustworthy by Google’s Search Quality Raters meaning that webpages will be ranked lower in Google Search compared to other authoritative, trustworthy sources.

To further support heuristic search and rely on the broader networked information ecosystem, Google introduced the Knowledge Graph feature in 2012 to present facts about entities (e.g. people, places, events) at a glance, with the underlying data being pulled from Wikipedia (Singhal 2012). To help curate the quality of its crowdsourced content, Wikipedia refers to a dynamic list of reliable and non-reliable information sources compiled by their community of moderators and maintains a running list of Controversial Issues to protect sensitive pages against biased information and “edit wars”. Newsrooms are also becoming increasingly aware about the importance of responsible and timely reporting on sensitive events in a decentralized online information environment.